In an exclusive interview with Earth.Org, Professor Johan Rockström, the lead scientist behind the planetary boundaries framework, discusses how recent climate trends are worrying the scientific community and the importance of adopting a new global governance approach that protects and preserves the regulating functions of the Earth system, critical for life on our planet.

—

For more than a century, scientists have monitored climate trends and provided governments, businesses, and stakeholders with the understanding necessary to shape modern human lifestyles in a way that benefits both economic development and human well-being.

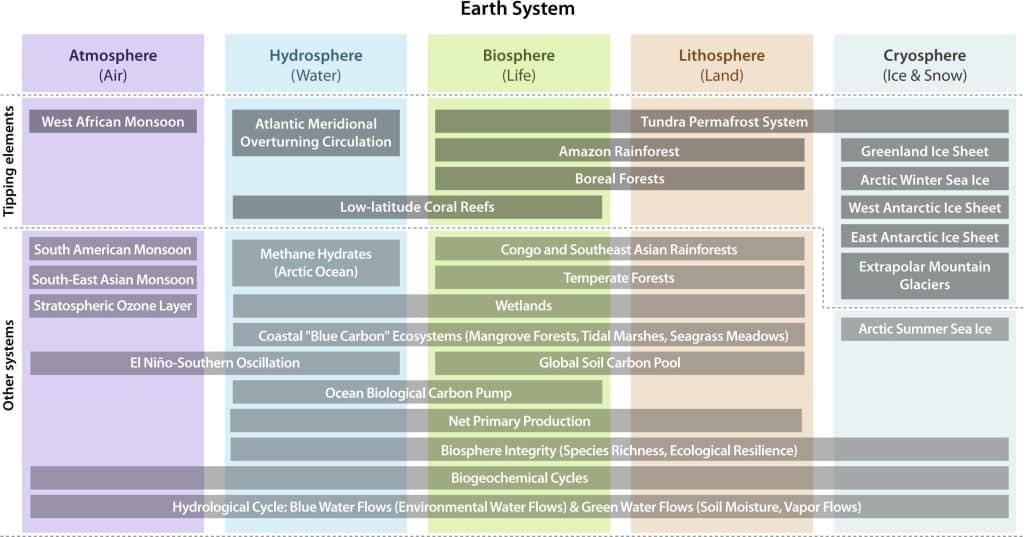

During the 1970s, scientific understanding of Earth systems increased tremendously and in the decade that followed, evidence of climate change began spreading. Since the establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988, the scientific community began looking at the planet with different eyes – as a complex, self-regulating bio-geophysical system characterized by interconnected spheres – lithosphere (land), hydrosphere (water), biosphere (living things), and atmosphere (air).

At the same time, scientists began developing an understanding of tipping points, multiple stable states of an Earth system that, if pushed too far, could result in unstoppable, permanent, and irreversible changes in the state of that system. For instance, continuous external pressure on a system like the Amazon rainforest, the world’s largest and richest biological reservoir and one of the most important natural carbon storage systems, can turn the forest into a savannah and a source of carbon dioxide.

More on the topic: The Tipping Points of Climate Change: How Will Our World Change?

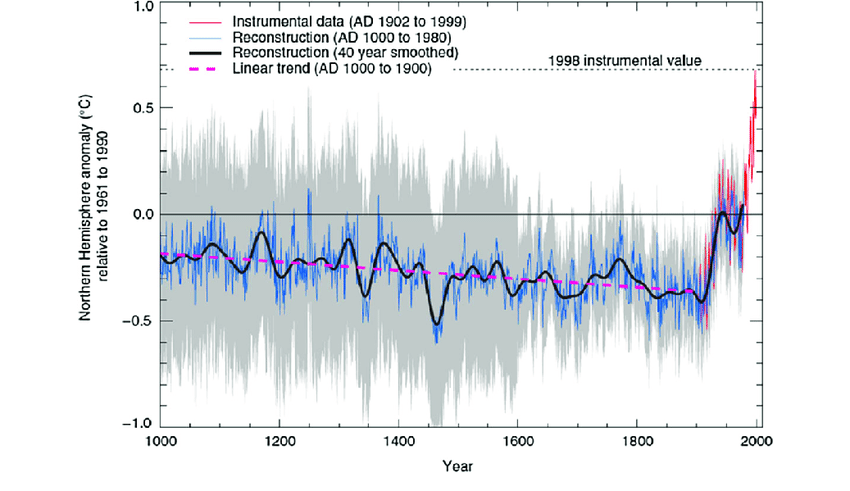

A turning point in climate science came in 2001, when the IPCC featured in its Third Assessment Report the popular “hockey stick” graph, an illustration of the changes in global temperatures of the past millennium that revealed an unprecedented, sharp upward trajectory towards the end of the 1990s and into the new century – the “blade” of the hockey stick. While the graph does not specifically attribute this increase to fossil fuel emissions, it aligns with the broader scientific consensus that human activities, including the burning of fossil fuels, have been a primary driver of the observed global warming trend.

All the evidence gathered in the course of four decades left scientists with two key questions: What are the biophysical processes that regulate the state and health of the planet? Once identified, could we quantify safe boundaries that give us a good chance to keep the planet in a liveable state – but beyond which we risk causing a drift away from that state?

“Answering these questions was the next inevitable step in climate research at that point,” said Professor Johan Rockström, who sat down to speak with Earth.Org while on a visit to Hong Kong to attend the One Earth Summit in March 2024.

Rockström is the director of Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and lead author of the planetary boundaries framework, an important body of climate research that has generated enormous interest within the fields of sustainability and environmental policy. The framework has served, and continues to serve, as a valuable guide for policymakers, urging them to consider the long-term consequences of human actions and adopt strategies that prioritize the sustainable use of Earth’s resources.

‘Danger Zone’: The Consequences of Transgressing Planetary Boundaries

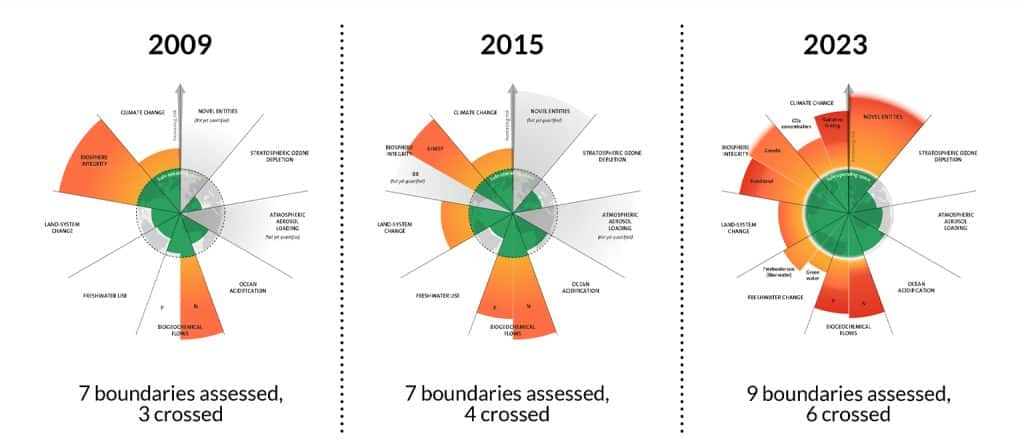

First published in 2009, the planetary boundaries framework defines and quantifies the limits within which human activities can safely operate without causing irreversible environmental changes. It does so by identifying several critical Earth system processes and defining thresholds – or boundaries – that should not be exceeded to maintain a stable and sustainable planet.

The framework consists of nine interrelated planetary boundaries: climate change, biodiversity loss, land use change, freshwater use, ocean acidification, ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosol loading, chemical pollution, and the introduction of novel entities. Each boundary represents a specific aspect of the complex biophysical Earth system that is essential for maintaining a stable and habitable planet.

“Boundaries are set to avoid tipping points, to have a high chance to keep the planet in state as close as possible to the Holocene, that allows it to maintain its resilience, stability, and life support capabilities. Go beyond and we enter a danger zone… the uncertainty range of science,” Rockström explained. In 2023, he and other scientists at the Stockholm Resilience Center in Sweden published an update of the framework. The study found that six of the nine planetary boundaries are already transgressed, placing the Earth “well outside of the safe operating space for humanity.”

“Unfortunately for climate, six of the nine planetary boundaries are operating outside the green space… with a high risk of triggering irreversible changes,” Rockström said.

To better understand the “danger zone” scenario, it is worth looking at an example.

Both ocean- and land-based ecosystems are dominated by what scientists call “negative feedbacks,” any processes or changes that act as buffering systems, regulating the planet’s functions and keeping it in a healthy state by limiting or reducing the impacts and severity of an initial change.

“Feedback processes are what we measure with planetary boundaries. Keep them in the green to remain at the right side of the fence, go into the danger zone and they start wobbling.”

Concretely, these processes are found, among others, in forests and oceans, both of which have the extraordinary capacity to absorb and store about 25% of the carbon dioxide (CO2) present in the atmosphere, respectively. Oceans also capture about 90% of the excess heat generated by these emissions.

“These absorption rates combined are the biggest subsidy to the world’s economy. It means that half of our climate debt is hidden under the carpet of a forgiving planet,” Rockström explained. “We enter a danger zone, and these systems start to misbehave.”

This is the case for some parts of the Amazon biome – the world’s single-largest carbon stock – which, according to a 2021 study, is now releasing more carbon than it is absorbing. “It is no longer helping us, it’s becoming a negative force,” he said.

Similarly, the Greenland ice sheet, capable of reflecting around 89% of incoming heat from the sun back to space, has experienced unprecedented melting for decades due to the relentless rise in global temperatures, and it is now melting at double the rate at the beginning of the century. This affects the reflectivity power of the ice sheet: as melted water becomes darker, it begins absorbing heat instead of reflecting it, a process known as ice-albedo feedback.

“The moment a system absorbs more than it releases, it has crossed a tipping point and you cannot stop it. It goes from a cooling to a self-warming system,” explained Rockström.

So far, human activities – primarily the burning of fossil fuels – have increased global average temperature by 1.48C; this, however, represents a mere 2% of our heat contribution. The remaining excess heat is absorbed by and stored in the world’s oceans (89%), stored in land masses (5-6%), and about 4% is available for the energy-intensive melting process of ice and glaciers.

“It’s a huge paradox,” said Rockström. “One of the biggest threats to humanity [melting ice] hides more warming than the fossil fuel emissions we’ve caused so far. Imagine what would happen if ice disappeared.”

“This alone is enough to explain the significance of the planetary boundaries.”

‘Shocking’ Trends

Early understanding of the anthropogenic impacts of human activities on the planet did not lead to the fundamental changes our society needed at the time to prevent the situation from worsening further. Thanks to our inaction in recent decades, we now find ourselves in completely uncharted territory.

“Humanity has opened the gates to hell,” United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres told the UN General Assembly in 2023, warning that “humanity’s fate is hanging in the balance.”

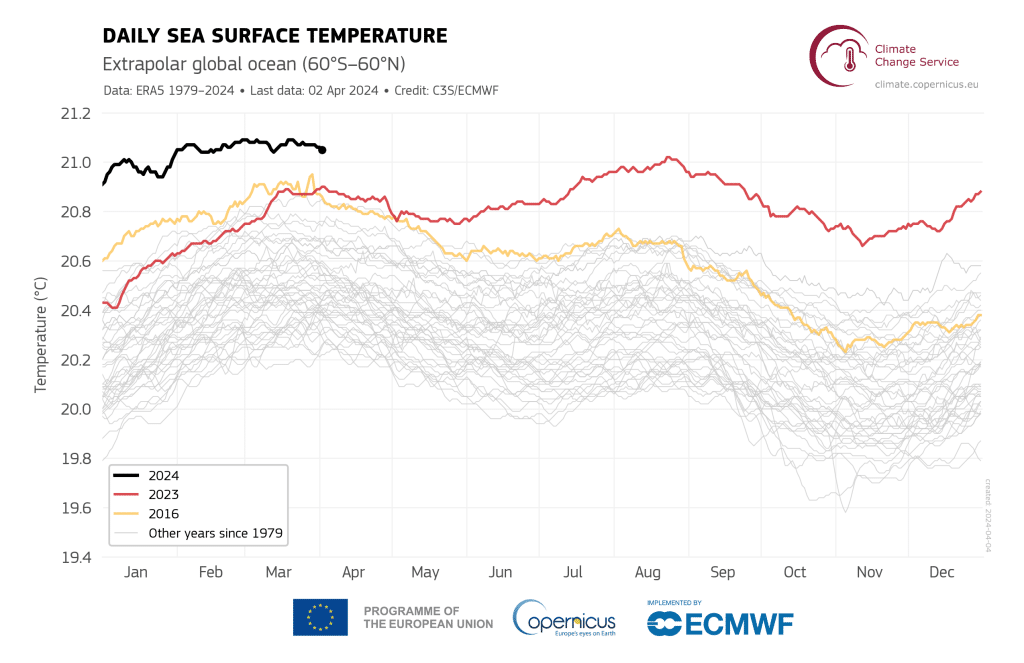

The past nine years have been the hottest on record, with 2023 topping the ranking. Last year’s record-breaking temperatures can be partly attributed to the return of El Niño, a weather pattern associated with the unusual warming of surface waters in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean. However, despite scientists confirming the gradual weakening of the pattern in recent weeks, the trend has continued well into the new year, with this past winter as a whole setting new high-temperature marks and March 2024 marking the 10th consecutive hottest month on record, both in terms of air and sea surface temperature.

What’s even more worrisome is that climate scientists are struggling to understand or explain these trends, which climate scientist Zeke Hausfather last year famously described as “absolutely gobsmackingly bananas.”

“We had seen El Niño conditions before, so we expected higher surface temperatures [last year] because the Pacific ocean releases heat. But what happened in 2023 was nothing close to 2016, the second-warmest year on record. It was beyond anything we expected and no climate models can reproduce what happened. And then 2024 starts, and it gets even warmer,” said Rockström. “We cannot explain these [trends] yet and it makes scientists that work on Earth resilience like myself very nervous.”

Recent data also show a relentless rise in global sea temperatures, which have doubled since the 1960s.

“There has always been the assumption that the ocean can cope with this, that the ocean is able to absorb this heat in a predictable, linear way, without causing surprise or any sudden abrupt changes. Up until 2023. Because suddenly, temperatures [went] off the charts, and that’s what is so shocking,” said the Swedish scientist.

Ocean warming has potentially huge implications for marine ecosystems such as coral reefs and coastal communities. What we are witnessing in our oceans, Rockström explained, has never been observed before and could be “a sign of collapse.”

“Has the ocean tipped over? We simply do not know. We don’t know if we are causing permanent changes. One thing we do know, unfortunately, irrespective of whether it’s a permanent change or not, is that it is virtually certain that this will knock over all the tropical coral reefs systems.”

Coral reefs are extremely important ecosystems that exist in more than 100 countries and territories and support at least 25% of marine species; they are integral to sustaining Earth’s vast and interconnected web of marine biodiversity and provide ecosystem services valued up to $9.9 trillion annually. They are sometimes referred to as “rainforests of the sea” for their ability to act as carbon sinks by absorbing the excess carbon dioxide in the water.

Unfortunately, reefs are disappearing at an alarming pace. According to the most recent report by the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN), the world has lost approximately 14% of corals since 2009.

In April 2024, scientists confirmed that the world is undergoing its fourth global coral bleaching event and already the second in the past ten years. “As the world’s oceans continue to warm, coral bleaching is becoming more frequent and severe,” said Derek Manzello, coordinator of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Coral Reef Watch (NOAA CRW). “When these events are sufficiently severe or prolonged, they can cause coral mortality, which can negatively impact the goods and services coral reefs provide and that people depend on for their livelihoods.”

Toward a New Global Approach to Safeguard Planet Earth

The planetary boundary framework was designed not only to define the environmental limits within which humanity can safely operate but also to guide global sustainability policy development and inspire meaningful action on a national and international level to ensure that these boundaries are not transgressed.

At the core of this is a newly established paradigm that Rockström and other scientists worked on for years and presented to the world in a paper published in January 2024.

In light of recent climate trends, the team revisited the long-standing “global commons” concept, a framework that regulates the governance of four planetary systems: the atmosphere, the high oceans, outer space, and Antarctica. These systems are non-rival, meaning they are not owned by anyone and do not fall into a national jurisdiction, and non-excludable, meaning no one can prevent anyone from accessing them.

But as Rockström put it, the global commons system “is no longer enough” and it is time the international community adopts a more effective and comprehensive approach that safeguards critical regulating functions of the Earth system.

For this reason, the new approach suggests complementing the existing framework, which only takes globally shared geographic regions into account, with an additional legal entity: the planetary commons. The new paradigm incorporates all “critical biophysical systems that regulate the resilience and state, and therefore livability, on Earth” and that we collectively depend on for life support, irrespective of where we live or where they are located. These systems include tipping elements such as the Amazon rainforest, the Greenland ice sheet, and the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC).

“It is quite a revolutionary paradigm, but entirely consistent with planetary boundaries science. It changes the game entirely.”

The main argument in favor of the new approach is establishing a regulatory framework to govern planetary commons on an international scale, given that their benefits and contributions are far-reaching and extend well beyond national borders.

A great example of this is the Amazon rainforest, which spans across nine nations and 3,344 formally acknowledged indigenous territories. While being an important national asset, the rainforest also supports a myriad of ecosystem services, acting as a huge repository for Amazon countries and humankind.

This sentiment was echoed in Brazil’s Minister of Environment and Climate Change Marina Silva’s speech at last year’s UN climate summit in Egypt: “Protecting forests means protecting the balance of the planet and the oceans… Commitment to the forest is not just from the government. It’s about business, society and science. And we work with all these pillars – because protecting the forest is not just a government action, it is an action by all of humanity.”

“[President] Lula and Marina da Silva understood this very clearly before our paper was even published. Planetary commons have to be governed and protected by the international community. I’m as keen to keep the Amazon rainforest intact as an indigenous Brazilian community,” said Rockström.

Future Outlook

Despite all the science available, climate progress on a global level has been remarkably slow, putting the world off track on its climate targets. All three main greenhouse gases reached historic highs in 2023 and according to the most recent data, the world has now just around six years left before it runs out of the carbon budget required for a 50-50 chance to keep the global temperature rise below 1.5C.

“The reason why [scientists] are using stronger and stronger language… is that we’re running out of time, not that the evidence is changing so much,” Rockström argued. He said no credible study shows us that we can achieve the 9% yearly emissions reduction needed between now and 2030 and the only chance we have at achieving that is by “doing everything right on nature, phase out fossil fuels, and get serious on carbon dioxide removal.”

But by far the most effective way to do this, he argued, is carbon pricing, a policy approach aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions by putting a price on CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions. So far, the European Union’s price is among the highest in the world and the nearest one to the social cost of carbon (SCC), an estimate of the economic damages that would result from emitting one additional ton of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, which a 2022 study put at around US$185 per tonne of CO2.

“Every economist hates subsidies and [carbon pricing] is the biggest subsidy in the world. But that would be the fastest way [to reduce emissions]. Put a $200 price tag on carbon dioxide, give all that money to a Loss and Damage fund, and off we go.”

Featured image: One Earth Summit.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us